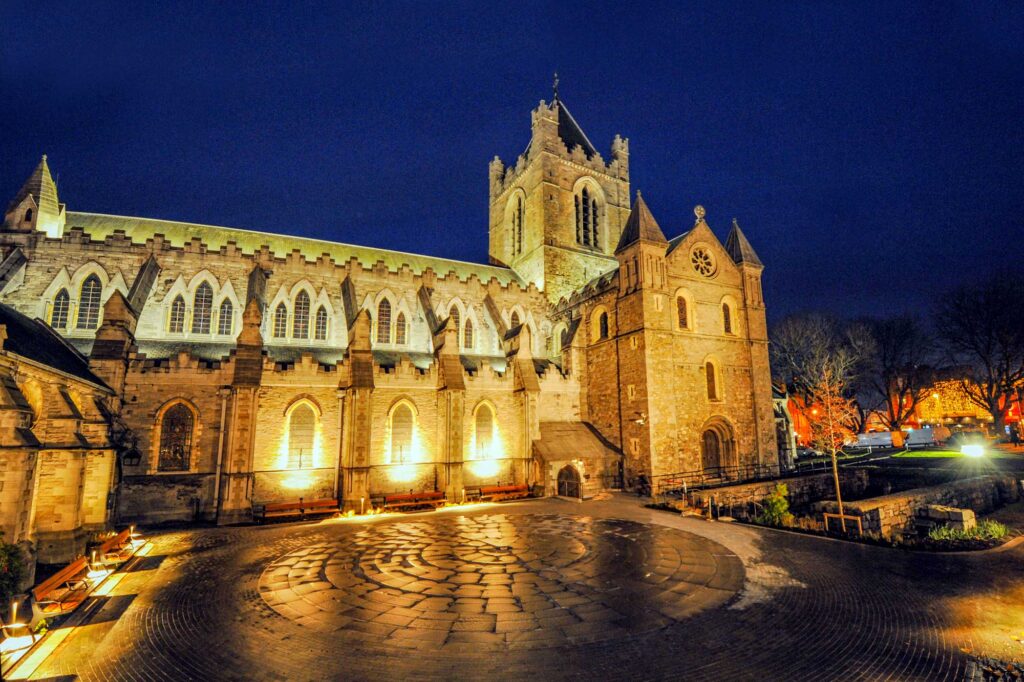

Christ Church Cathedral. Advent I. 6 Dec. 2015

Mark 13:7: When you hear of wars, and rumours of wars, do not be alarmed; this must take place, but the end is not yet.

Humankind has suffered rumours of wars, and wars themselves, from its beginning. The Bible is full of them; and in our own generation we have known plenty. Just as I was beginning my ministry, the Cuban Missile Crisis blew up, and at Theological College we fled from the TV screen to the chapel in horror and fear. And this week we have seen the spectacle of a British Prime Minister crying havoc and letting slip the dogs of war.

But this is not the place to go into the political rights or wrongs of that decision. Someone said on the television the other night that we needed to face up to the basic differences of belief on the two sides of the present conflict between near east and near west, between the world of Islam and the world of modern Europe, both secular and Christian. Both worlds are divided in themselves; both have their extremists and their moderates.

In a few moments, we shall be standing up and saying together, ‘I believe in one God’. Our Jewish and Muslim friends also believe in one God; and if there is only one God, presumably we worship the same God – but we see that God through very different spectacles.

The question is: What sort of God do you believe in? Do you, for example, believe in a tribal or national God, a God who defends your tribe, your nation, your territory, against all comers? That is the God of the Old Testament, who would send plagues on Egypt and drive out the Canaanites before the Israelites. Or do you believe in a God before whose unknown will all must bow, and accept whatever comes as God-given, as ‘min Allah’, as the Muslim say, ‘from Allah’, and therefore unarguable? Or do you prefer a God represented on earth by a young man whose concerns seem to have been for the poor and those on the edge of society, and whom the Romans crucified as a dangerous revolutionary?

How you conceive your God affects the way you treat society and how you treat those who do not believe as you do. Conversely, the way you treat society and people with different beliefs reveals what sort of God you worship.

Christianity, at least, does not believe in treating ordinary people as if they do not matter. It does not believe in bombing other human beings made in God’s image. It does not believe that everything in this world – sickness, present social structures, injustice, even slavery – has to be accepted as part of the divine will. Christianity does not believe that those who do not share the same approach to God must have their heads cut off as evil heretics. Christianity is prepared to see that Judaism and Islam and Buddhism and other religions including worshippers of nature have all understood at least something of the glory of God, and is able therefore to converse with them.

But what Christianity finds hard to cope with, even within its own ranks, is those who believe that their own simplistic theology is the divine answer to everything; those who resist the advance of scientific knowledge and western philosophy as hostile to God; those who demand simplistic creeds by which others may be judged and controlled. Such fundamentalism, which appears sooner or later in every religion and is particularly evident within both Islam and Christianity, is hard to take. It is dangerous because it does not make for loving people, however much it talks of the love of God for them. We prefer to think of Jesus, in a phrase popular when I was younger, as the man for others, a man who showed God’s love in the way he treated others. God is love, says our Christian scripture; and the religion of love survived the Roman empire and survived the northern gods of the Vikings and will survive other imperialisms, whether political or religious, and will survive the pressures of this secular age, though perhaps not in the particular structures we know and love.

Now I know that to say that does not provide the political answer to the political problems of this week; but it does give us an over-view of where as Christians we have to start. It suggests to begin with that welcoming migrants from this world’s trouble-spots is much better than dropping bombs on them, and that constructive dialogue, even with people whose fundamentalistic view of God is far removed from our own, is in the end absolutely vital; there must be understanding of people with totally different religious mind-sets, however difficult that is. Christianity, above all religions, must strive for peace, must work to bring people of different minds round one table, and eventually break bread and share wine together. That symbol of bread and wine, taken under the shadow of crucifixion, under the misery of foreign Roman rule, is a most potent symbol of what Christianity is. That is a symbol of our belief and approach to life. We may hear of wars and rumours of wars, but do not be alarmed; the end is not yet.